Photo: Press (Miss Djax)

Saskia Slegers wears her legacy on her sleeve, literally speaking. Dressed in a Djax Records longsleeve, her down-to-earth attitude creates somewhat of a stark contrast in the otherwise the aesthetically shrill design hotel she is staying in. The walls are adorned with glittering portraits of pop stars, and in the somewhat tackily designed bar area someone plays acoustic guitar to a mildly interested audience sipping on cocktails, waiting to leave and enjoy some of Berlin’s nightlife activities. Not far from here, Slegers played on the most important gigs of her life at MayDay 27 years ago. It would make Miss Djax internationally known for her uncompromising, belting techno sound. She regularly played at the city’s annual Love Parade while releasing many records on Djax Records that are now regarded undisputed classics. Tonight, she is in the city to play Berghain for the first time ever as part of the 20th anniversary of CTM Festival.

It’s not the only birthday being celebrated this year. The legacy of Djax Records, founded in 1989, is currently being cherished by the Dutch Dekmantel label with a compilation series comprising classic material. For Slegers, the round anniversary however is not per se special, she points out. Even though is in high demand these days, she knows very well that hypes come and go. „If the hip thing is over in a few years, I’ll still be doing this,“ she says. „Sometimes you’re hot, sometimes you’re not.“ Still she enjoys meeting new fans who were not even born when she released some of the most seminal records in dance music, or having the chance to share the decks with old friends. The name Miss Djax is almost synonymous with persistence, which somewhat fittingly is CTM’s motto this year. Her contribution to our Groove podcast proves even further that she herself hasn’t lost a iota of energy throughout the past 40 years she has been standing behind the decks. It is of course, a belting all-vinyl mix that serves as a reminder that this is a DJ who has the terms „TR-303“ and „Techno“ tattooed on her forearms.

Tonight’s CTM event is called As If We Were Free. What does that mean to you – freedom?

For me, it means that you can do what you love, when you follow your heart. Freedom of expression, freedom of musical choice, the freedom to make your decisions and to follow your own path. It’s a luxury if you can do that because if you were born on the wrong side of the world, you do not have much to choose and you do not have much freedom. We’re all lucky to have what we have in this democracy. For me personally, with Djax, it is about following my path – which I’ve always done. I have never cared if I would sell any of the records, if people would like it or not. I liked it, so I signed and released it.

As a record label, Djax has always been stylistically very diverse. It is remarkable that you released so many hip hop records, even though as a DJ you came from funk and disco via electro and hip hop to house.

(laughs) I was asked that question a lot back then – ‘How can you do hip hop and house together’? It was two different scenes back then and they did not fit. Hip hoppers didn’t like house and some house heads didn’t like hip hop. But actually – hip hop, hip house, there was a connection of hip hop growing into house. But like you said, I started with playing disco in 1979 when there was no house yet. I entered the house scene in a completely different way than many other DJs. Sometimes interviewers ask me, ‘How did you get into house music? In which club did you hear house for the first time, which DJs did inspire you?’ None of that! In the eighties I was working in a record shop and I always was looking for new stuff for the shop, which was an underground store. That was how I got into new music, also for my DJ sets – I was always looking for new styles, new things happening. It was a logical progression for me from disco to funk to new wave to EBM to electro, hip hop, hip house etc. It was an evolution that led to house and acid techno. I liked hip hop, so the first Djax release was a hip hop album. Then I discovered a group rapping in Dutch, which I found very special because nobody was doing that at the time. Very explicit lyrics, I received a lot of comments on that. ‘How can you release that, it’s female-unfriendly!’ The Dutch radio even boycotted it. But it was something new and something different – why not give it a chance? There’s a huge scene in Holland now for Dutch hip hop.

That was the first so-called Nederhop release. Do you still follow that scene?

No. I stopped around 2001 because Nederhop was getting really commercial and going in a direction that was totally not my thing. The stuff that I released was raw, underground and hard.

You haven’t stopped running Djax, but kept a very low profile since the early 00s.

That was partly because of the digital era. When the CD came, vinyl sales were already low. CDs are not my thing, you know, and then the internet came – illegal downloads, and all that. It wasn’t interesting to me anymore to run a large record label because you don’t work towards a physical product anymore. Nowadays being a record label is uploading tracks online and do social media stuff. Once in a while I release something, on vinyl or digital. A few weeks ago I released a new EP from Junk Project, but it’s only digital.

Sure, but there is a market for vinyl.

Since a few years it’s coming back yes, vinyl is hip again, but still you don’t sell much and it takes so much time to press a record now because the pressing plants are overflown with all those re-releases from major labels which sadly causes that the underground labels, of which many never stopped supporting vinyl, have to wait up to four months maybe to release them – and then sell around 300 copies at best. Also the prices at the pressing plants keep on raising. A digital release goes much faster, you can get it in the online shops within a few days. But the problem is that every week thousands of tracks are being released on the internet which will already be forgotten in the week after. Everybody is making music, everybody is DJing.

And how is it with your own productions?

I’m not doing much at the moment, the last album was Flight 303 three years ago. This year I will release a 12” for the 30th anniversary of Djax. I’m thinking of some sort of anthem, maybe together with Junk Project, one of my favourite acid producers from Germany. But I never plan something. When I feel like doing it, I will do it, but if I don’t, I don’t. I didn’t plan a lot of things for the anniversary, because I see it as just another year. I’m not too attached to these kinds of things.

What then makes you go into the studio?

I must feel that I want to do it, I have to be inspired, but at the moment I don’t have so much time for it because I’m doing a lot of other nice things. I also like to travel, not the traveling that I do as a DJ, but to explore the world. I also like to photograph. I was thinking of DJing less but the requests keep coming and coming. I was hoping it would slow down, but it doesn’t! It’s probably due to the nineties revival. (laughs)

What drew you to DJing in the first place? You were still a teenager when you decided that you wanted to do it.

Just to be the chain, the connection between new, exciting underground dance music and the audience. That could be as a DJ in a club or on the radio, or by working in a record shop, playing in a band or running a record company. I did all those things. It was about hunting for new music and letting people hear it.

But you have said that you haven’t been buying new music for years now.

Yes, that’s true. laughs. In the last 5 years, I have only been buying a few new records. The reason is that I have so many great records from the nineties which I am still playing that I decided that I don’t need anymore new records. Also for the new generation ravers that come to my gigs, these old records are new. And because I only play vinyl most new stuff is not suitable for me anyway because it’s only available in digital format. But as I said it’s no problem because there is enough amazing music from the nineties out there.

But don’t you sometimes feel like going to a record store, hoping that something there will surprise you?

Of course I sometimes do that, but then where do you find me? In the classics section! (laughs)

But you probably have all these!

That’s true, but sometimes I find stuff that I do not have and also I didn’t keep all my records. And some records I need to buy again because I played them so much that they are not useful anymore – I am not so careful with my records when I play. (laughs) I am not a collector, my records are my tools so they get really used. But sometimes I’m curious about recent acid stuff, like Regal and Boston 168.

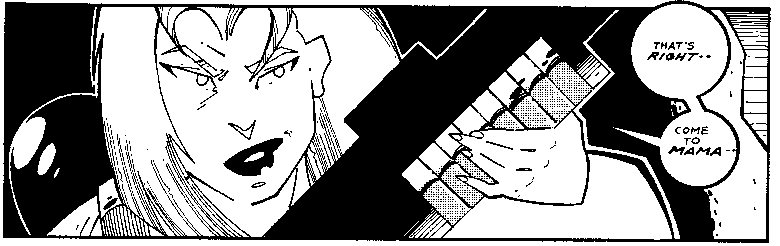

Throughout the past 30 years, you have mainly worked with Alan Oldham as an illustrator, which gave Djax a very coherent aesthetics. What is your working relationship like?

That’s a long time, isn’t it? It all started with a demo he sent me under his Signal To Noise Ratio alias. I saw the name and was like ‘Ah! That’s the guy who does the illustrations for Transmat!’ I told him that I wanted to release his tracks (the Detroit Is Burning EP was released in 1991) and asked him if he wanted to do illustrations for Djax. He agreed and made hundreds of them until today, including five comics. It was very easy to work together in the nineties. There was no internet, but connections were easily made. When I went to Chicago and Detroit, I met everyone. I would just phone up or fax people telling them I’ll be in Detroit and if we could hook up somewhere. So we did, exchanged records and talked for a bit. Nowadays, that seems hard!

Why that?

There’s too much of everything! Too many labels, too many DJs. Some DJs now have managers or other people in between, they receive too many e-mails and messages. It’s too much! Before, it was just the phone, and everyone knew each other anyhow. You had Derrick from Transmat, Richie and John from Plus 8, Mike Banks and Underground Resistance, Jeff Mills…

A tighter scene than today.

Very tight! It still is when you see each other now. It’s something that stays forever. That’s a good feeling, it’s still special because you have a bond. And many of them are still playing – Laurent Garnier, Carl Cox, Richie… Everyone is still on the road!

It must be exhausting however, to be on tour consistently for 30 years.

It’s not like you’re 30 years on tour. Of course in the nineties, I was going somewhere every weekend, Friday and Saturday, to this country and that country. And then from Monday to Friday, I would take care of the record label. Every Friday, I would take home a huge box of demos to listen to at home. It was a really hectic time. Every day when I would come into the office, there were meters of fax paper all over the floor and it took a whole hour to check the answering machine. Nowadays I only spend a little time on the label. I am doing my bookings by myself, and it’s a maximum of three weekends a month. I don’t want to play every weekend anymore, so I must really say no to a lot of offers. That’s also a sort of freedom!

The freedom to say no – something that a lot of young DJs these days do not feel they actually have.

I think for today’s DJs it’s really hard to set yourself apart and stick out. There’s just too many, which therefore makes it hard to stick out – everybody has a label, everybody is a DJ, everybody is producing music. Back in the days, when you didn’t have the records, you couldn’t play them. And if you got the promos, you and maybe ten or 20 other DJs had them, too, at best. Now you can go online, find a list of all the classics, download them and play a classics set. Very easy. There’s not much evolvement in that.

But how could techno possibly evolve?

That’s always the question, isn’t it? In the beginning, everybody was saying ‘Ah, in ten years this will be over!’ and ten years later everybody said that it would be over in ten years from then. How can it evolve… It’s logical that things go in circles, that everything goes back to the best or to the beginning but then maybe a bit slower or faster or harder or more minimalistic. It moves in waves. Acid is very hot again at the moment. But how can techno evolve? I don’t know! So much has been done already.

But your fascination with acid still persists. What drew you to it?

I think the trippiness and strangeness drew me to it. The… (imitates an acid sound) It’s different and spacey. I’ve always liked things that were different and I still love the trippiness of it. Even without drugs, because I don’t do drugs.

How is it to have a completely sober experience of an audience which is, well, not sober at all?

(laughs) It’s fine with me that they are on drugs because they probably have a very deep experience, although I don’t need it all. The acid sound is enough already. I was never someone who would go to parties to stay for eight, ten, twelve hours. I also haven’t been drinking any alcohol for years, so I’m totally clean. The music is the drug for me.

Follow Miss Djax on Facebook or check out her website. Junk Project’s Relapse EP is out now digitally on Apple Music and Beatport.

Stream: Miss Djax – Groove Podcast 200

01. The Art of Trance – Cambodia (Trope Remix)

02. Random XS – Give Your Body

03. Phuture – We are Phuture

04. Acid Masters – The Unknown

05. Science Wonder – Phrequenzy

06. Riccardo Rocchi – Acid Pill

07. MisjahRoon – Shake your Ass

08. Essential Age – Essential Age

09. Peacemaker – Adventures

10. Aquaplex – Instinct

11. DJ Misjah – Cocaine

12. Major North – Annihilate

13. Tetra Pack 2 – Life line

14. Laurent Garnier – Wake Up

15. Voyager 8 – Transistor Rhythm

16. Yaka Suki – Power Cult

17. Ovilon – Coded Message

18. I/D – White Label

19. F.U.S.E – F.U.

20. Aquaplex – Victim