Klickt auf diesen Link für die deutsche Version des Interviews.

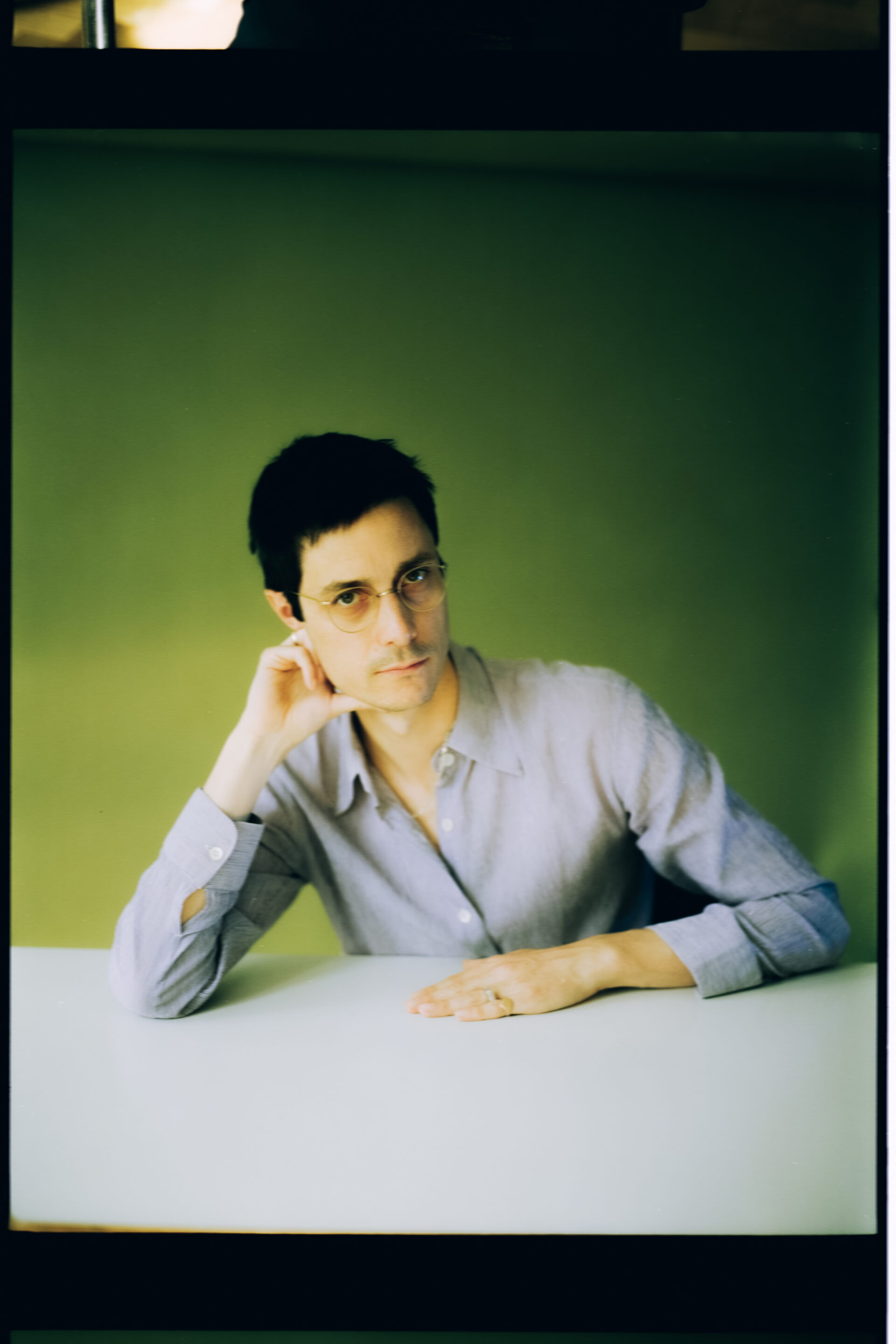

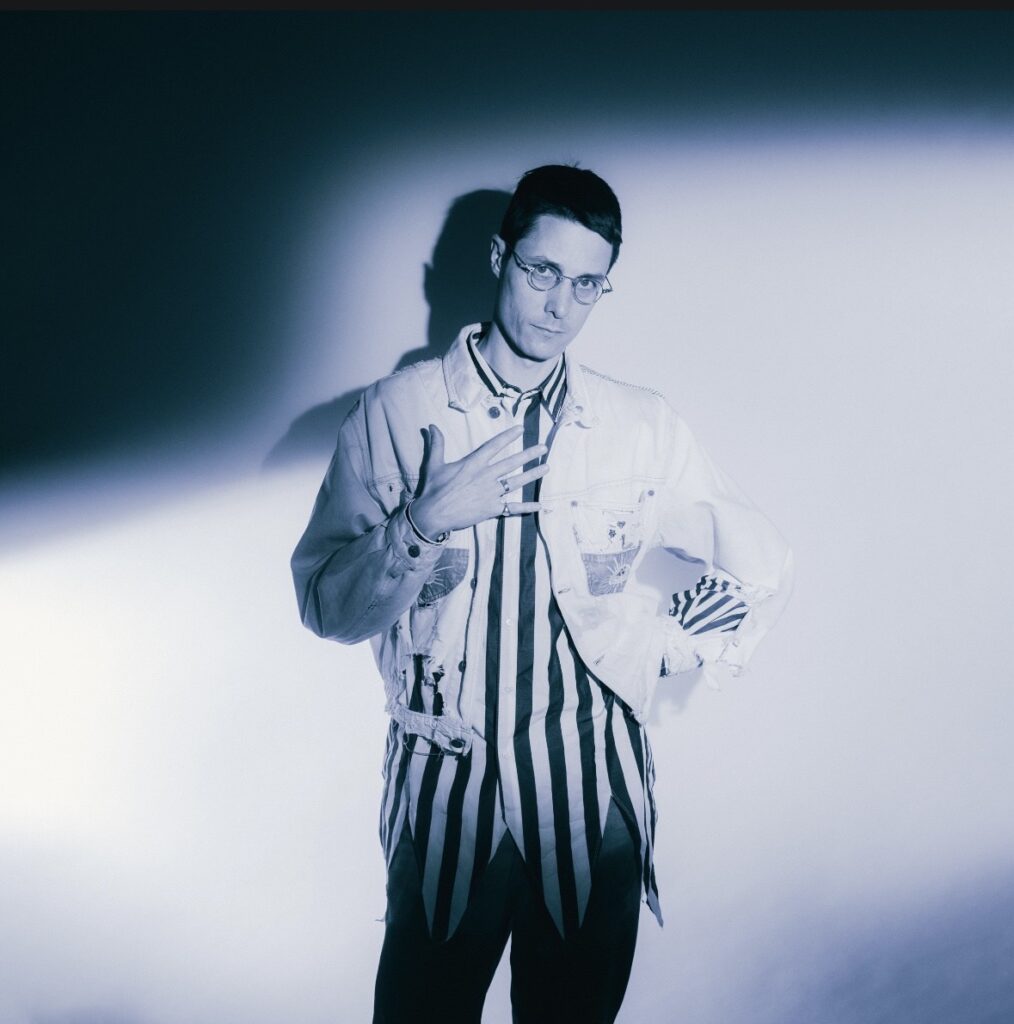

Call Super is one of the many aliases of Joseph Richmond Seaton, a DJ and Musician from London. Their previous albums have defined an individual place in the electronic music scene, creating adventurous and experimental playgrounds, going far beyond the club walls.

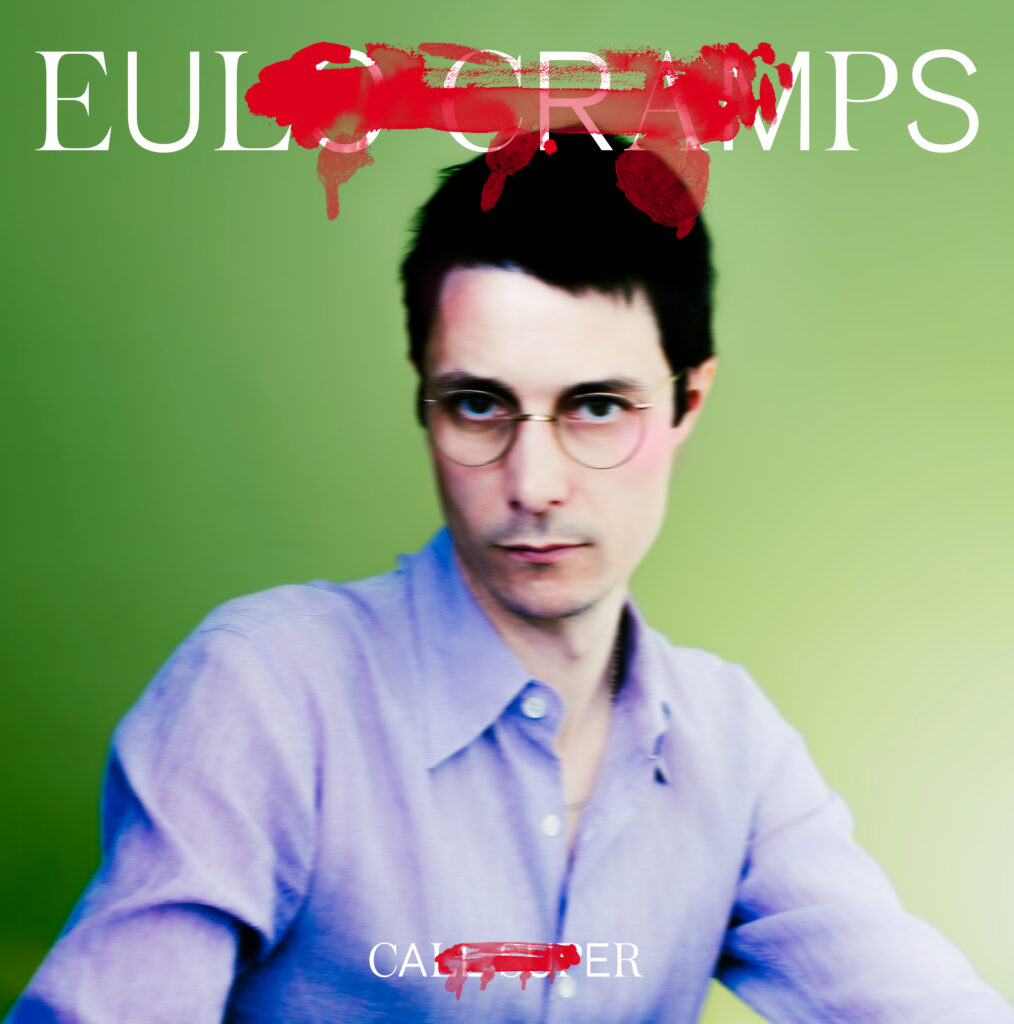

Earlier in October Call Super’s fourth studio album Eulo Cramps was released via Can You Feel The Sun, a label led by themselves, and their colleague Parris.

Eulo Cramps is characterized by its personal depth: Rooted in their experience of the Corona pandemic, Seaton’s sensibilities flow into the album and make it appear human and naturally calm. Featuring among many guests Seaton’s father on the saxophone, backed by broken beats, improvisational jazz, ethereal voices and Call Super’s use of the e-harp, the album’s theme evolves as a reckoning, with trauma and revelations of their own coming-of-age story.

Multimedial aspects reveal themselves in an exhibition at St. Mary’s Church in London in November and December, which was created as part of the album and is named Tell Me I Didn’t Choose. Seaton’s artworks express their ideas more deeply within Eulo Cramps, the canvas serving as a physical space for self-discovery.

Ameera Lumb talked to Call Super via video call on a Wednesday morning. Seaton jumped on the call while staying in California, where they took a break from touring with longtime friend and fellow artist Objekt.

GROOVE: Joseph, you were busy with gigs this summer. Recently, you also had your most personal studio album Eulo Cramps out. How are you doing?

Call Super: This year feels more manageable than last year, where I felt really close to a breaking point. After the pandemic, going from what had been a very introspective time, I was thrown back into a high intensity schedule. Now, I’m being very conscious of keeping space for myself.

How do you feel about Eulo Cramps?

I’ve put out records in the past, and this one feels the most like me as a person. That’s reflected in the presentation of the record and how we, me and Dwayne Parris, have decided to present it. For example, the decision to do more press around it and speak more about the music. For the last album, I chose not to speak about the process at all, so that feels new and out of my control. But I also feel like I’m letting go and shaking off a lot of things that have lived in my head for a very long time.

How did Eulo Cramps come about?

It deals with a very particular period in my life, which I was reflecting on a lot. I went from quitting art school in London, because I wasn’t a fan of the art world, to finishing uni in Scotland, and finally moving to Berlin, trying to survive, get and make work for years. Then, my music career started to grow and quite quickly became intense. When I stopped in 2020 because of the pandemic, I had a lot of time to do the reflective work on myself that I had been lacking. In the previous years, there had been a lot of painful stuff. Difficult, traumatic experiences I had gone through as a teenager, that I needed to return to and begin to unpack, to understand who I was and what they had done to me. I developed a way of understanding life that made a lot of sense to me.

How do you see life?

It’s not like you or I are on a journey to become this real version of ourselves. We are many versions of ourselves throughout our life. And these are all perfectly true and valid and authentic. The people that we haven’t become yet are within us, the people that we were are still within us. They might be very faded, almost not there, but there are traces of them still there.

Could you elaborate on that?

We contain multitudes, they are always with us. Through that idea, the album developed. I was creating a visual representation of these ideas, writing poems to get the ideas out a bit more. From there I developed a sonic language for these things and a way I wanted to express these ideas in music. And that’s really the genesis of this project.

When did you start working on Eulo Cramps?

I began working on the first track in early 2019. The way I work is that there are lots of ideas for different projects going on in my head. Sometimes, I’m really focused on one thing, sometimes I’m doing bits of work on lots of different things. Eulo was a thing that I worked on up until sometime in 2022, when I finished it. It’s something you have months of intense activity on and then periods of pause.

Is it hard for you to finish something?

For some people it’s really hard and for other people it’s very straightforward. I think I’m somewhere in the middle—that’s the nature of my work. A quality I want my work to have is to be very, very stylized and finished in some ways and oddly unfinished in other ways.

Are you a perfectionist?

I just have this sense, I keep working on something and working on something and working on something. And at some point I say “No, I think this is it”. I think you need to have a clear vision of what this thing is meant to be.

Did it just become your life’s work in the process, or was it your intention from the beginning to create something depicting your journey of life?

It came pretty early in the process. Here was a record where I wanted to involve my own mental experiences as an early teenager. Then I added the guitar, because the acoustic guitar is an instrument I practiced a lot, and also the piano. I also wanted to have some kind of fictional instrument, which, for me, was somewhere between the two. I was making this sound, which sounds a bit like a guitar but with strong strings.

Is that the e-harp you invented?

Exactly. That’s the idea for that.

What is the meaning of the album name Eulo Cramps?

I have an album called Suzi Ecto. Ecto is a state of bliss for me, like an abbreviation of the word ecstasy. The next album was called Arpo, which was a kind of oblique reference to Harpo Marx, who’s the forgotten Marx brother and had this strange life.

Eulo Cramps returns to this naming scheme. Cramps are something people get when they’ve done something to a point where their body can’t do it anymore, or they can’t get enough oxygen into a particular muscle to keep it working. Cramping is a stage that we hit when the threshold of an experience breaks.

And Eulo–it’s very simple: You are low. Once you get a little bit older in life and you have a chance to reflect on times and experiences that have formed you, I think you realize that you can’t be a solid person who can handle the things that life throws at you, without going through a lot. It’s not a depressive thing, I see it as an important thing.

It seems there are many layers to the title.

You can unpick it in certain ways, but I also just wanted it to be a name. It’s not like you need to know what the meaning of something is to appreciate it. If you really appreciate it and you want to scratch a bit further, though, there’s something to scratch at.

“I like the idea of it all being a blurry mess.”

Call Super

What about the name Call Super?

[Laughs] I really hate that name. But it stuck somehow. It came from my dear friend TJ [Hertz, editor’s note], his artist name is Objekt. It started off as a dumb joke, because he’d made a record and he didn’t know what to call it. So he just stamped “Objekt” on it and everyone just thought it was his name, but it wasn’t. Then it stuck.

And your name?

I was also in the position of having a record to release that following year, so I was looking for names. Programming contains something called antipatterns. These antipatterns unpick your work. You have to find out what’s wrong in the code and these things are called Call Supers. You’ll find a much better explanation than I am capable of on Wikipedia. But that’s the original genesis of that name.

Eulo Cramps, Suzi Ecto, Elmo Crumb: They all exist, because I wanted to come up with names I liked, as I was stuck with this name that I hated. I realize that my main name has currency, but I like the idea that people aren’t too precious and play about with identity, otherwise it just becomes very streamlined and careeristic. I just write music, and sometimes I’ve had fun putting out different names, I don’t have any separation between anything.

How did you come across your guest vocalists, and what did the collaboration mean to you?

Elke Wardaw and I met 10 years ago, because we live next to each other and I’ve always loved her voice. She’s from Baltimore and has the best accent. I wanted to put that in the record somewhere. Julia Holter–I’m just a fan. I really love her work and reached out and she was up to doing something together. Eden Samara is someone who I got to know through mutual friends in London. She asked if I’d do something for her record, so I did. I got to know her and she has a rich and powerful voice. A lot of singers these days are crooners, they go for this very close-mic, soft, vocal style. Eden’s got a proper rooted-in-her-lungs, chesty voice, which is super rare.

I wanted there to be a range of a few different things, I didn’t want to work with a well known singer, I wanted to have something a little bit more personal. I hope that comes through in these choices. Sometimes the economy of ambition is all you need.

The album is about self-expression connected with nature: What do you see in nature? How does it compliment you and your music?

I don’t know. I grew up in a city, I’m not someone who’s lived in nature, but I feel like I’ve always needed it. I want my music to be an extension of myself and to have this quality, that’s very human. Human qualities are deeply connected to nature. We grow and we are organic beings, made of cells like plants and everything else. I find it quite hard to say why my music sounds the way it does, but I know it has something to do with that. The connection to being a living organism, like everything else on this planet.

Do you use nature to recharge yourself and your creativity?

Not really. I love spending time in it, but I’m actually terrible at taking holidays and getting out of the city. If I have a weekend off, I am much more likely to be in a bar with a friend than by a lake. I think the answer for all of these things is just in trying to make sound truly reflect me. Some people sit down and say “I want to write an electro track” or “I want the music to sound futuristic”, I don’t think anything like that. I just think: I want to express who I am as a person and create this little world that is me.

What do you mean by that?

This way of thinking comes from my arts background. If you’re a painter or illustrator, the way you make marks on the paper is totally you, your work is an extension of who you are. That’s how I approach music making and always have done. It’s always been there. My studio process is very much one that lets in the ambient sound. My favorite thing to listen to is the world around me. I spend long periods in the studio, then get out and don’t want to listen to anything at all to balance that out. Then I spend more periods in the club, that’s very nourishing in its own way. But then I need to balance that out with the opposite: early nights and mornings and quietness, around me, and all the rest.

Have you struggled with balancing yourself between club and quietness?

I started my music very young, but I wanted to keep music as a hobby and do something else in life. But as the years went by, the music started to form into this career. It wasn’t until I was in my 30s, when I had these pressures on. Some years were hard and I struggled with it, but I always knew who I was. That’s the main thing. I see people who come into it young, and have an identity crisis after a few years, because they haven’t done the growing up that we all need to do outside of something quite public.

When did you say: “Okay I’m gonna close all the doors on anything else and focus on music”?

I was working in a call center in Berlin and was very sick of it, so I decided to try and get a better job. So I applied for a BBC apprentice program. At the same time, I was discussing a deal with Houndstooth, and thought: “Look, either I just take a punt on this and throw myself full time into music or do the apprenticeship.” So I just went for it. I was around 24.

Let’s start from the beginning: What was your first encounter with music?

Probably my dad playing his instruments. We listened to music in the car a bit. I remember a lot of Tracy Chapman, and the jazz that he listened to. People like Sammy Rimington and Ken Colyer, Louis Armstrong or Bob Dylan.

And your own personal encounter?

It’s hard to say, because I started playing the guitar when I was five. From the age of eight, I started doing recitals, concerts and stuff. The first album was one my uncle bought me for Christmas, the White Album by The Beatles. That was my first music I owned. Music that I actually went out and bought myself, was probably from Leaper or Suede, one of those 90s bands. I was also into Pulp. But it’s hard to know. I feel like my own journey into music was very much through playing it rather than being a fan. I played for years before I started buying music.

How did you come in contact with electronic music and club culture?

I started playing in bands when I was about 10, and the friends I had would listen to bands in the UK in the late 90s. They were indie bands, but influenced by dance music. My best friend’s older brother would go raving to hard techno and trancy stuff, so we got tapes and CDs off him and sat in his room when he let us. Around the age of 12 to 13, I suddenly found electronic music fascinating. I connected deeply with the fact that you were able to make music on your own, without needing a band. Being in bands is fun, but it’s also frustrating, if you actually have lots of ideas yourself. Just understanding how emotional electronic music can be. That was liberating.

When did you start DJing?

I got my first pair of decks for my 15th birthday. I had 500 pounds given to me by my godfather. That was enough to get very cheap decks.

Do you remember your first gig?

Me and two friends did a little night in a place called Cafe 1001 on Brick Lane. Out front, it was an ice cafe, and in the back, there was a club. They let us do something in the front bit. We were 18. Just about legal. I also worked behind a bar that had decks in. When I finished my shift at that bar, they would let me play records until two in the morning. Later on, when I was studying in Scotland for a while, I started getting actual gigs in clubs and doing student radio stations etc.

Did you DJ before producing?

I did not release anything for years. It’s so important to have a period in your life where there’s no great ambition. You’re just DJing because you love doing it. It gets lost, a lot of people think “I want to do that next year”, like ok, best of luck. You need to treat everything with respect. Often, people who make electronic music get looked at quite cheaply, because people think they’ve gotten very far quite easily. I’m a romantic, I think there will always be a place for the patient worker.

What’s the hardest place to DJ?

Hardest is when you’re playing in a fairly busy space, and no one seems interested in anything. You’re second guessing yourself the whole time.

And where do you feel most comfortable?

The easiest is, when that connection happens right away, and by the end you’re truly as one. Houghton felt like that this year.

“Dance music is full of cheap tricks and shallow repetitive ideas. Sure, sometimes they’re fun, and sometimes they’re annoying.”

Call Super

Your music is known for breaking the borders of modern electronic music. Has anything annoyed you in club culture that made you want to change it?

When you look out at any kind of cultural landscape, be it in club music, theater or ballet or cinema, you’ll see lots of work you just don’t particularly connect to, that you think is rubbish. All I hope is that, if I make music professionally, there is space for the kind of things I like. Everyone is just into something completely different. I don’t look out there and think “look at that music that I hate, it’s gonna inspire me to make something different.”

But?

The longer you’re in this, you see people who did one thing and then clearly got massive ambition, so they just stopped and did something totally different that’s trendy at that moment. People just want to be as big as they can be. I’ve never really connected to that and I often think the music that comes out of that kind of thing is not very good. We’re talking about dance music, it’s full of cheap tricks and shallow repetitive ideas. Sure, sometimes they’re fun, and sometimes they’re annoying.

Does it make you sad that the majority of people would think “that’s good”, because it’s easy listening?

The majority of people are not into the best thing in my view, but that’s because I like different stuff. I’ve also been conscious of growing as an artist, you need to be careful, because you don’t want a huge audience. You want your audience to feel connected to the ideas you have. My hope is that the world can hold all of these things and everybody gets a chance to do their own thing. It’s my job to go out and find the stuff that inspires me. Just ignore the stuff that you find annoying, let it go and move on. There are a lot of great people out there doing good stuff, focus on them.

There definitely are. Who are your inspirations? Specifically for your studio music versus your DJ selection?

When I’m at the studio, I listen to a lot of music that I think about playing as a DJ. And when I’m at home, I listen to a lot of music that is really not dance music led. It all feeds into the music I write. I loved that James Holden album that came out earlier in the year. I think that’s one of the best things he’s ever done. I’ve also been listening to a lot of folk music, Michael James and Terry Reid. What’s interesting about the folk scene in the 1960s and 70s is, there was a whole queer side to it, particularly lesbian folk artists in America. And a lot of it was linked to real community work, building spaces for people to form communities around. Joan Baez built a whole community in a political sense. They became some of the first explicitly queer community spaces. At home, I spend a lot of time with music like that.

What’s the last album you bought on Bandcamp?

Christina Vantzou, Michael Harrison & John Also Bennett, a sweet raga-inspired composition.

Any newcomer you have your eyes on?

Mainly because of her DJ sets: Katiusha, based in Berlin. She did one track on the last Peach Compilation I really liked.

How would you start a career in music if you were starting out today?

You have to be a very, very yappy dog. Just constantly snapping at it with ideas. That wasn’t a very good analogy, but you do have to have a very clear idea. It needs to be a continuous path. There can’t be a dam or stoppage anywhere on this path. The water just has to flow. That is something that hasn’t changed. The things that have changed are the methods of communication and the media, and all the rest of it.

You said earlier, you didn’t want to be in the art culture, and left art school in London. Now you are hosting an exhibition connected with your album release. So you are in the art world.

Figuring out how to present this stuff in a way that wasn’t linked to galleries or money was quite a nice task. The way I decided to do it, was to do it in a church. I went to church every week until I was 11. The reason it’s in St. Mary’s church is because the vicar is an old friend. The other decision was: The only thing that will be for sale is a little book for around 20 euros. It is affordable and not speculative — the opposite of the art market.

Does the exhibition have a religious connection?

No, I’m also not religious myself. But I don’t have a particularly negative view of religion, which I think a lot of people do. I see it that the vast majority of people who go to church, just get a sense of community out of it. At the end of the day, that’s why people go and do bowls on a Sunday or play cards with their friends. Obviously, most of the conversation around religion seems to be focused on fundamentalist stuff, but I think it’s actually a fairly benign force.

“Take your time. don’t try to run before you can walk, it will help you in the long run.”

Call Super

Any advice?

My main piece of advice is just always be a listener. Someone who is going out and having these experiences with music. All of that will feed into anything professional coming your way, and the more you have to draw on, the more you have to talk about and connect with people. Everything seems overwhelming, but the point is, a lot of people burden themselves with pressure and try to rush things. You don’t really want an avalanche of success before you know how to respond to it. What you want in life, is to be able to take the opportunity when it comes along and feel like you were in just the right place. You don’t get these opportunities often in life.

What was your moment of opportunity?

I didn’t know it at the time, but looking back: the slot I did at the Dekmantel Selector stage in 2016. After that things felt different.