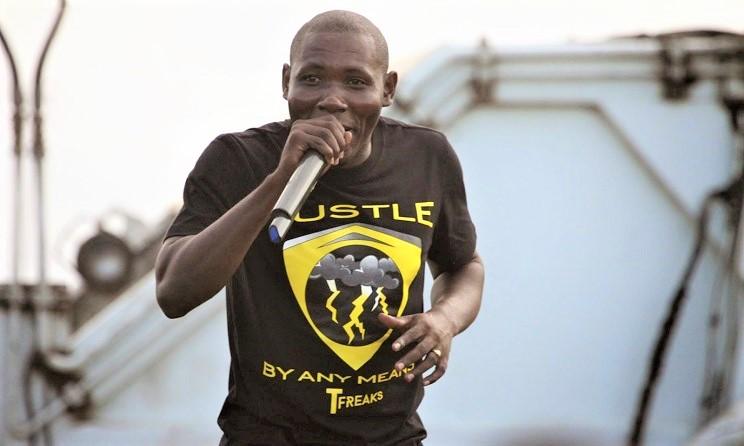

Nyege Nyege Festival (photo: Nyege Nyege)

Nyege Nyege shaped a platform which enabled the electronic music scenes from all over sub-Saharan Africa, facilitating an exchange not known before as much as empowering artists to gain access to the global festival scene. Lucy Ilado explains how the festival was able to achieve this and why some artists nonetheless feel excluded by some of the festival’s most current policies.

An icon of electronic music and hailed as the “godfather of electronica,” French composer, performer and record producer Jean-Michel Jarre once likened the music genre to an act of preparing food. He said: „For me, electronic music is like cooking: it’s a sensual organic activity where you can mix ingredients.“ This idea has proven to be true in Africa, where young producers and DJs are mixing traditional sounds backed with a strong electronic undertone.

Although the genre has in the past decade gained popularity and is soaring to new heights, the love affair between electronic music and the continent dates back to over 50 years ago with its long tradition of experimental, body-moving electronic music composition. Some of the well-recognized pioneering musicians include William Onyeabo from Nigeria, Ata Kak from Ghana and Bony Bikaye from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Presently, many African DJs and producers have gained global recognition such include Ibaaku from Senegal, Black Coffee from South Africa, Slikback from Kenya and DJ Rachael from Uganda, among others. Their desire to conquer dance floors has put the continent on the international electronic music map. Apart from the artists, African festivals have also played a massive role in popularizing the genre to both local and international fans.

Nyege Nyege Festival – The Irresistible Urge to Dance

Nyege Nyege festival is one of the world’s most well-known electronic music festivals that’s held every November for four days at the Nile Discovery Beach in Jinja. The event programmes both local and international acts on seven different stages that allow the festival-goers to enjoy both live bands and DJ sets. There’s nothing that East Africans love more than having a good time. All you need is to throw in some music, a dance floor, good food, a vibrant atmosphere – a perfect Nyege Nyege festival. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 restrictions on public performances, the 2020 edition was held virtually between the 3rd and the 6th of December. The festival ran under the theme of African Unity and was streamed via the Nyege Nyege website with a line up of 300 artists from across the globe.

Nyege Nyege was founded in 2015 by Burundian Derek Debru and Greek-Armenian ethnomusicologist Arlen Dilsizian. They established the festival to contribute to the growth of the music scene and also to bring international visibility for the artists. Debru, who has a background in film and politics, first arrived in Kampala by invitation from a friend who was working in the country. Before he had been to Côte d’Ivoire „working on a video production project that fell apart due to political turmoil,“ Debru says.

He later met Disizilan, and the two began running the Kampala Film School and subsequently started hosting events and being involved in the music scene. „Music has always been a part of my life“, Debru says. „I used to organize performances for my parents and their guests with my little sister. Tina Turner, James Brown and Whitney Houston were some of the favourites of those days if I remember. I got into electronic music through house music, especially the scene in Japan, where I studied and lived in my early twenties.“

The pair later used their savings and launched the first edition of the Nyege Nyege festival in 2015. Although they incurred many losses, somehow they managed to grow their audience every year consistently. They also developed partner relationships with various local companies such as MTN Uganda, the largest mobile telecom company in the country.

„We wanted to set up a concept that is interesting and different from the electronic music that was coming from the rest of the world,“ Debru says.

In 2016, Debru and Dilsizian launched the Nyege Nyege Tapes record label for electronic music from East Africa. At the time, this style of music was considered „outsider“. Generally, in the region, any sound outside the pop music chat gets ignored or given only a cursory glance by the mainstream media.

Debru says the idea behind the label was to increase cross-fertilization of African music with European underground dance sensibilities; a development they felt was being neglected in the African festival circuit. Four years later, the festival is recognised as a high point for international collaborations and exposure. Together with the labels, it is now home to several emerging, forward-thinking, creative and ambitious young underground artists spearheading change in a region where opportunities for experimental sounds are limited – local media and music promoters have been slow to embrace them.

„I would like to see the mass media take more interest in promoting music which is not necessarily per se commercial because it can never be commercial if it doesn’t get the airplay that it deserves,“ Debru says.

„An artist like Slikback [from Kenya] has created a category of his own, carving a unique sound that has made so many waves amongst connoisseurs, not to getting more attention in Kenya is surprising. So you can see how the festival has helped artists to gain more recognition locally. Most of those that we programme are rarely the same ones who perform in other large events, so our platform has become essential and respected.“

At the same time, there are a few artists affiliated to the Nyege Nyege who have managed to make waves outside the continent, the duo Otim Alpha and Leo Palayeng being an exception. They have had successful performances across Europe with Germany and France being the first two places to take them in.

Debru says that even though the duo does not receive the same attention locally, electronic music enthusiasts acknowledge their role as the custodians of Acholi folk songs, which are at the brink of extinction, through the fusion of tradition and electronic music.

„Otim Alpha is the greatest performer on the planet. At the age of 51, I’ve never seen someone as captivating,“ Debru says. „His performance is a direct injection of goodness and happiness and energy, into your body and your soul, you can’t resist it. He’s been praised by so many yet still I believe he deserves a breakthrough locally.“

Another top artist from Uganda is DJ Kampire who was among the first DJs to play at the festival’s first edition. She has gained recognition outside the continent for her unique production of African themed electronic music that can be heard across her releases. Her sets include high-octane tempos and twisting polyrhythms achieved through the fusion of sounds such as Latin bass, St Lucian soca, Congolese soukous, Afro-house, baile funk, kuduro, gqom, and many other undefinable genres.

„As our greatest ambassador, friend, co-founder of the festival and pillar of our collective, Kampire’s music is ever developing and changing, but always with a great sense of groove and love for African rhythms far and wide,“ Debru says. „What I love most about her is that her music touches everyone, if you ever have a crowd with very diverse tastes, put in a Kampire mix and see the joy coming from people’s legs.“

Other DJs on the rise are Catu Diosis from Uganda and Coco Em from Kenya. These three are the most recognizable female faces in the country’s electronic music scene, especially for youngsters who need to convince their parents that a career in DJing is worth it. They are giving way to a feminine revolution that starts from dedication, talent and, above all, good music. The reality is that, in most festivals, the number of women artists is below 10%. While there is no exact data on how many women hold positions of responsibility and decision in festivals and management agencies, those who work in the industry say that the figure is equally ridiculous.

According to Debru, one of Nyege Nyege’s core missions was to establish gender equality more deeply through the festival lineup. But generally, all the festivals in the region are looking to programme more female musicians. Change is undoubtedly happening with the region looking forward to a future where music will not be the “pale, male and stale” playground any more.

„Nyege Nyege has drawn a lot of attention to artists in the region,“ Debru says. „It has widened an existing network of bookers, music journalists, festival programmers, label heads, distributors, that lead to more opportunities for artists.“

Victim of Moral Policing

Nyege Nyege festival has contributed to the number of tourists that visit the country as well. Each year, the festival, directly and indirectly, offers employment opportunities to more than 500 people, prioritizing local personnel for crucial roles in food vendors, artist management, administration, media, security, cleaning, technical, ticketing and merchandise. Ironically, despite its contribution to the local economy, the festival does not have official backing from religious leaders and local authorities – they have been accused of contributing to the erosion of African “social norms.”

In 2018, Simon Lokodo, the Ugandan Ethics and Integrity Minister, accused the festival of promoting homosexuality, a sexual orientation deemed un-African by some of the older generation.

„I have received credible information from religious leaders, opinion leaders and local authorities that the purpose of this festival, in the last two years, has been compromised to accommodate the celebration and recruitment of young people into homosexuality, and LGBT movement,“ Lokodo wrote in the letter.

Lokodo continued: „Nyege Nyege will not be accepted because these people will be openly saying such statuses. This year, it will not take place. I wanted Nyege Nyege cancelled last year, but they escaped. There will be nudity and sexuality done at any time of the hour. There will be open sex. The very name of the festival is provocative. It means sex, sex or urge for sex. This is close to devil worshipping and not acceptable.“

Fortunately, the organizers managed to get a permit to proceed with the event. Many critics considered this intervention by the Minister ironic because, under Uganda’s Constitution, all individuals and organizations have the right to associate freely in private and in public, without fear. It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that human rights of all citizens, including LGBTI citizens, are respected and protected.

Nyege Nyege festival and the singeli sound from Tanzania

The Nyege Nyege Festival is credited for having popularized singeli music outside its country of origin. The sound is a genre of African electronic music from Dar es Salaam and is informed by decades of the country’s folk music. The first hit of a singeli song rushes through a crowd like a shot of adrenalin, with the ladies stealing the show with the Chura dance – a type of Tanzanian twerk. The beat is fast – between 180 and 300 BPM – integrating drums, bass, shakers and synths.

The genre is linked to Africa’s long tradition of experimental, body-moving electronic composition. It has since spread to Europe, championed as one of the most exciting emergent strains of dance music in 2018, thanks to the Sounds of Sisso compilation by Sisso Records based in Dar es Salaam, released last December via Nyege Nyege Tapes. Some of the singeli artists Sisso Records include Bwax, Sisso, Bampa Pana & Yung Keyz Morento, Mc’s Dogo Niga and Makaveli – they are the only ones that have managed to tour abroad.

Popular singeli music promoter popularly known as Meneje Kandoro says the genre has spread around the ghettos in Dar es Salaam for almost 15 years.

„It’s rowdy and uniquely Tanzanian,“ he says. „Despite its huge following, the artists are yet to penetrate the East African market. The media might front pop genres like bongo flava – the most popular pop genre in the region, but it’s singeli that is played in clubs across the country seven days a week.“

He continues: „COVID-19 has proven that singeli artists are the kings of the dance floor. Unlike other African countries, Tanzania did not have any lockdown. We continued with our routine: work during the day and party at night. However, we noticed a decrease in the number of shows organized by pop artists because they heavily depend on sponsorships and partnership with companies that suffered losses due to the lockdown in the neighbouring countries. On the other hand, singeli artists have had shows non stop. The reason for this is that singeli artists depend on the people and not sponsorship. One of my artists, called Msaga Sumu, plays at three different clubs in a night and gets paid well.“

„The regional media is yet to pick on the music. We also do not get as much coverage as we would want from the local media. But, there are few artists – those affiliated to Nyege Nyege festival – that have managed to perform abroad.“

However, beneath all the glorification that Nyege Nyege has received, there have been complaints about poor artist’s fees from some East African artists and promoters that have either previously played or booked artists for the festival. One Kenyan musician who spoke on condition of anonymity said: „They do not pay artists well. I remember travelling by road and crossing the border only to receive 100$. I play at a local club twice a month and receive even more.“

As much as it’s not uncommon for festivals to ask artists to donate their time or play for much less than they might typically receive, many festival organizers try to programme fewer artists to ensure fair remuneration of artists, especially those that play live music. The festival scene in East Africa is not self-sustainable – organizers majorly depend on sponsorship and donor funding to organize and pay artists. In this case, to be able to minimize costs, priority is given to artists that can pay for their transport to and from the festival’s country.

Since its launch, Nyege Nyege festival has undergone a slight shift in programming that could be viewed as a strategy to accommodate more artists that were capable of raising funds for their travel and sometimes accommodation. In the beginning, the organizers programmed more live bands from the continent. Still, over the years there was a shift from that culture and it gradually evolved into programming more DJing showcases with a considerable number originating from outside the continent.

Pointing out some of the deficits of Nyege Nyege does not mean electronic dance music in East Africa is not structured a little more each year; it seems that the bubbling of this musical current has only just begun. With the continuous interbreeding of sounds, we can expect good years of musical production ahead of us.

This article is part of the Global GROOVE: Electronic Music Journalism series, hosted by GROOVE in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut. Read all other articles here.

About the author: Lucy Ilado is a music journalist and artistic rights defender in East Africa. She is presently the East African content editor for the Music In Africa Foundation, the largest resource for information and exchange in and for the African music sector. As an artists right activist, she spends some of her time facilitating and organizing knowledge transfer creative convening for social change. She has worked as a facilitator and organizer on promoting knowledge in democracy and creative activism.